|

History

Land

Beyond Punjāb

Deg Teġ Fateh

Archives

|

Sikhs, Jews, Jains, and Zoroastrians are frequently regarded as representing “world religions” despite the fact that they are much less numerous than Muslims, Buddhists, Daoists, or Christians. Of these smaller traditions, however, the Sikh Panth (“community”), with its twenty-five million adherents, is the largest. Its history started around 1520, when Nānak (1469-1539), a person of substantial socio-cultural capital, founded a town named Kartārpur (“Creator’s town”), and assumed the role of a Bābā (“leader”) for the families that gathered there. His assets included birth in an influential land-owning family; early education; exposure to administration at the village (Talvandī), district (Sultānpur), and provincial (Lahore) levels; and extensive travels in and around the region of his birth, which came to be called, beginning in the 1560’s, the Punjāb. Located on the right bank of the river Rāvī, with views of the Himalayan foothills in the north and east, the area around Kartārpur provided fertile soil, plenty of subsoil water, and abundant fauna and flora. The families that moved to the new town engaged in agriculture and followed the model of “truthful living” (sac acār) delineated in the poetic compositions of Bābā Nānak.

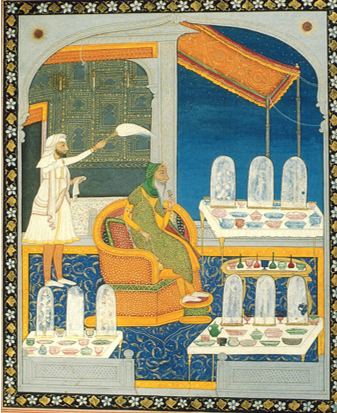

The earliest extant painting (mural) of Bābā Nānak (c. 1675)

In accord with a belief in the unity of the Creator (Kartār) and Sovereign (Sāhib) of the universe, and in the multiple way in which the creation (dunīyā) functioned, the daily lives of these families came to be oriented around the fundamental ideas of divine immanence (nām), social commitment (dān), and personal purity (iśnān). A set of institutions such as prayers at sunrise, sunset, and just before going to sleep provided daily markers of the community’s effort to keep the divine in constant remembrance. A shared meal (langar) following the prayer sessions manifested the belief in equality (age, gender, and social), and also provided an opportunity for communal service (sevā) and sharing the fruits of one’s labor (kirat) with others. Prayer sessions involved the recitation of Bābā Nānak’s compositions. These compositions were carefully recorded in a script organized specifically for this purpose, called Gurmukhi (“[of] Gurmukhs/Sikhs”) and were bound in the form of a book (pothī). The pothī (the repository of divine wisdom), Bābā Nānak (the bringer of this wisdom), and the Sikhs themselves, (“bearers of sikhiā” that is, the wisdom enshrined in the book”) constituted the three core points of reference in this nascent community.

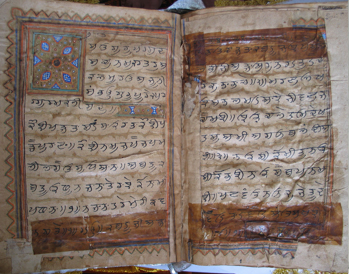

At the time of his death, Bābā Nānak passed on his pothī to Angad, his nominated successor, who led the community from 1539-1551. With time, the book's contents expanded to include compositions created by Nānak's successors, by bards at the Sikh court (darbār), and by saint-poets from both Hindu and Sufi backgrounds. Poems comprising this last group were selected on the basis of their conformity to Sikh beliefs. This sacred corpus, with its several parts, expanded in three phases around 1570, 1604, 1675, and reached its canonical version, called the Gurū Granth, in the 1690’s.

(pre-1539)

(pre-1539) |

(pre 1574)

(pre 1574) |

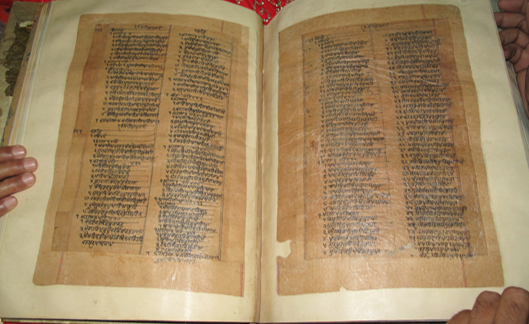

(1604)

The Gurū Granth

Other institutions established at Kartārpur also underwent elaboration and expansion with the growth of the community. Around 1600, external pressures from the Mughals in Lahore along with dissensions internal to the Sikh community were reflected in competing claims of leadership, which in turn served as the context for further strengthening the distinct religio-political identity of the community. The Sikh leaders were formally addressed as Patiśāh and understood to be responsible for both the spiritual and temporal (dīn/pīrī and dunīyā/mīrī) concerns of the Sikhs.

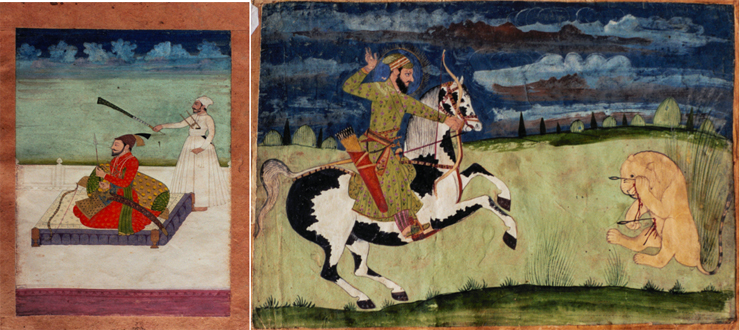

During the period of leadership of Gobind Singh (1675-1708), the tenth in the line of Bābā Nānak, two significant developments unfolded. First, the expanded text that started with the pothī containing Bābā Nānak’s compositions was assigned a canonical form. Secondly, the Sikh Panth was renamed the Khālsā Panth (God’s community), and its divinely-assigned mission was understood to be such as could bring about the Khālsā Rāj (“divine rule”) on earth. The symbols of deg (“cauldron,” food for all) and teġ (“sword,” justice for all) comprised the emblem that appeared on the Sikh niśān (flag) and on Sikh coins marking the Panth’s sovereignty (fateh).

The “Tenth Patiśāh” Gobind Singh (c. 1700)

The personal authority of the leader--Bābā Nānak and his nine successors--was gradually phased out during the period of Gurū Gobind Singh, the tenth Patiśāh, and at the time of his death he formally passed it on to the Khālsā Panth (bakś dīo khalas ko jāmā, Sri Gur Sobhā [1708]). The Khālsā Panth was expected to chart its future course according to the wisdom enshrined in the Gurū Granth (God’s book) and establish divinely ordained sovereignty (patiśāhī). While the status of the revealed word remained firmly intact, the mantle of authority (jāmā) that had been invested in the personal leader was assigned to the Panth. From this point on, mainstream Sikh thinking has been centered on the decision of the collective Panth. There has been a firm aversion to any claims of personal authority in religious matters.

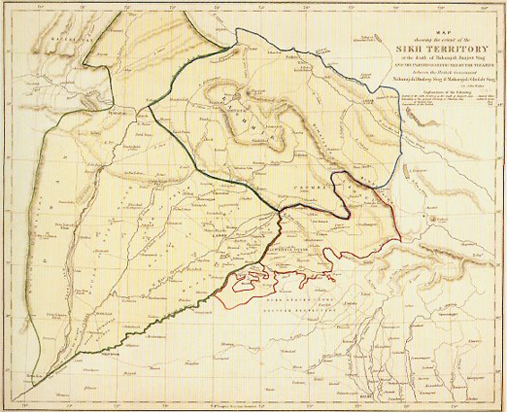

Within two years of the death of Gurū Gobind Singh in 1708, the Sikhs established political authority in the Punjāb, and developed the belief that the land of the Punjāb was a divine gift for them to rule. This vision attained its fullest realization under the stewardship of Raṇjīt Singh (1780-1839), when the Khālsā Rāj incorporated the three Mughal provinces of Punjāb, Multan, and Kashmir, with Ramdaspur/Amritsar and Lahore serving as the Sikh religious and political capitals, respectively. After Raṇjīt Singh’s death in 1839, however, the power vacuum thereby created and subsequent dissensions that emerged eventually paved the way for the British subjugation of the Khālsā Rāj.

Raṇjīt Singh (c. late 1830s)

Raṇjīt Singh (c. late 1830s) |

The Khālsā Rāj (1834)

The Khālsā Rāj (1834) |

These changed circumstances created a serious challenge to post-Anandpur belief in Sikh patiśāhī, a tension that continues to this day. Simultaneously, with the arrival of the British came also institutions of modernity such as the printing press and Western education. This period under the British has often been presented as a sort of renaissance, producing so-called “modern Sikhism.” There is, however, little hard evidence to support this position, and the precise impact of the Sikh loss of political power and the Panth’s response to modernity are matters that still need to be carefully assessed.

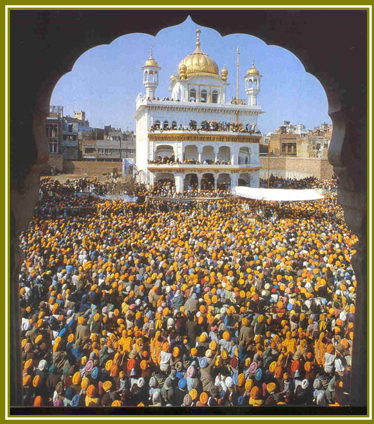

The departure of the British in 1947 and the partition of the Punjāb at the time sharply disrupted Sikhs’ self-understanding as a people associated with the land of the Punjāb. As the smoke settled following a huge loss of human lives, Sikh leadership found itself in a quandary. Adjusting the notion of sovereignty ingrained in Sikh consciousness to the demands of the nation-state of India posed a challenge that is still being worked out. Landmarks along the way included further divisions in the region; the showdown between Delhi and Amritsar during Operation Bluestar in June 1984; the assassination of Indira Gandhi, the prime minister of India, by her Sikh bodyguards; and the mass killing of Sikhs in Delhi and other cities in November 1984.

Akāl Takhat after Operation Bluestar (1984)

Akāl Takhat after Operation Bluestar (1984) |

Gurū Panth at Akāl Takhat (1987; c. M. Singh)

Gurū Panth at Akāl Takhat (1987; c. M. Singh) |

And yet, working for the British also created opportunities for Sikhs to move around the globe. After their police or army contracts were over, such Sikhs settled in new lands that extended from Fiji to east Africa to the Pacific coast of the United States. This movement continued after the British left the subcontinent in 1947, transforming the Sikhs into a global community. At the present time, the primary concerns of diaspora Sikhs include transmitting religious heritage to new generations of Sikh children; helping local mainstream communities to be better informed about Sikh history and beliefs; and building effective relationships between Sikhs who live abroad and the place they consider to be their Sikh homeland, the Punjāb.

|